Madison Seipp ’26, who is studying history, usually shies away from courses that involve engineering or the environment.

But Seipp signed up for Engineering, Empire and Environment anyway, figuring it must be a “cool class” because it was taught by Alison Fletcher, the W. Newton & Hazel A. Long Professor of History.

The course, which Seipp confirmed was cool, exemplifies Juniata offerings that embrace hands-on use of technology and connect to multiple disciplines, integrating liberal arts principles into technical fields. Fletcher decided to teach the course in response to Juniata’s burgeoning civil engineering and environmental engineering programs.

The final project required students to select an engineering feat from the British Empire and build their own three-dimensional model. They worked in close conjunction with Justine Kobeski Black ’08, director of the Statton Learning Commons, and Tom McClain ’94, assistant director of instructional technology. Students incorporated a wide range of technological advances into their projects, including micro:bit devices, 3-D printers, and a 14-foot-long riverbed simulator. They concluded their work by recording a short podcast about their project.

Fletcher shared that students selected a wide variety of projects, mentioning the Anglo-American Submarine Cable, U Bein Bridge, Crystal Palace, and Victoria Bridge, among others. “They had to tell a story about their project. The storytelling in many ways is at the heart of this.”

Seipp chose to create the Spitfire, the World War II airplane renowned for its performance and crucial role in the Allies’ victory. She came away with greater appreciation for interdisciplinary practices and enjoyed the way engineering, the environment and history intersect.

“Before this class, I was kind of opposed to learning about this new technology but now I see the possibilities of what it can create and do,” said Siepp. “It’s gotten me more open minded about how I view technology and use it in my day-to-day life, especially when doing academic work.”

Fletcher says the course worked well because it attracted students from diverse programs of emphasis. In addition to history students, the class consisted of students from environmental engineering, museum studies, accounting and STEM. Many had never done anything like the final project.

“When it all came together at the end, they were so excited by what they had created,” Fletcher said. “They wanted to show it to others, so I invited people for presentation day.

“I wasn’t quite sure how it would end up, but the students were amazing,” she said. “They were creative. They put in hours of work and had to do the research, the building, and then had to build a podcast and tell a story, which for me was very important.”

Seipp walked away with an additional benefit from the experience.

“I actually have a job now on the instructional design team [at the Statton Learning Commons],” Seipp said. “It kind of exposes people—both students and staff—to new technology we have on campus, especially in the library.”

There’s a river in the lab

Dennis Johnson, Blechschmidt Professor of Environmental Science, helps oversee a massive piece of technology acquired by Juniata in October of last year.

Two of Fletcher’s students used the Emriver EM4 Stream Table to examine water flow in their recreation of the Thames Embankment. The table, which can hold 70 gallons of water and 360 pounds of media, can simulate floodplains, deltas, groundwater processes and sediment transport. The students created a historical model of rivers in the United Kingdom and demonstrated the effects of tide and erosion.

“It’s a unique piece of equipment,” Johnson said. “To my knowledge there are only three or four in Pennsylvania and relatively rare for schools our size. We just ordered another nice piece of equipment—a flume—that will be added to the lab.”

Johnson plans to invite Juniata education students and host connection classes in the summer. He said students use the stream table regularly every week and are drawn to the water’s movement. “I always joke that if we put pizza and televisions in there, we’d never leave; we’d just sit there [and watch the water],” he said.

The ability to visualize effects and make hands-on adjustments is a game-changer for students’ experience in the lab.

“I can’t tell you how many times I see people in there,” Johnson said. “When the river is running, it’s mesmerizing. It’s pumping water and sand is moving, and the students are just laughing...you can take this [knowledge] from the lab to the field. ”

Johnson is also excited about a grant that will allow an increased use of drones by multiple classes, including geology, communications, and physics. Additional drones are on order as students learn how to become certified and licensed by the Federal Aviation Administraton.

“We did a course at our Raystown Field Station and ended up doing some really nice aerial photographs,” Johnson said. “We made a video on what it’s like to be at the field station. We’re going to grow our use of drones and several departments are interested in that.”

More in-house tech for hands-on use

Johnson isn’t the only faculty member who’s looking forward to students’ work with new equipment.

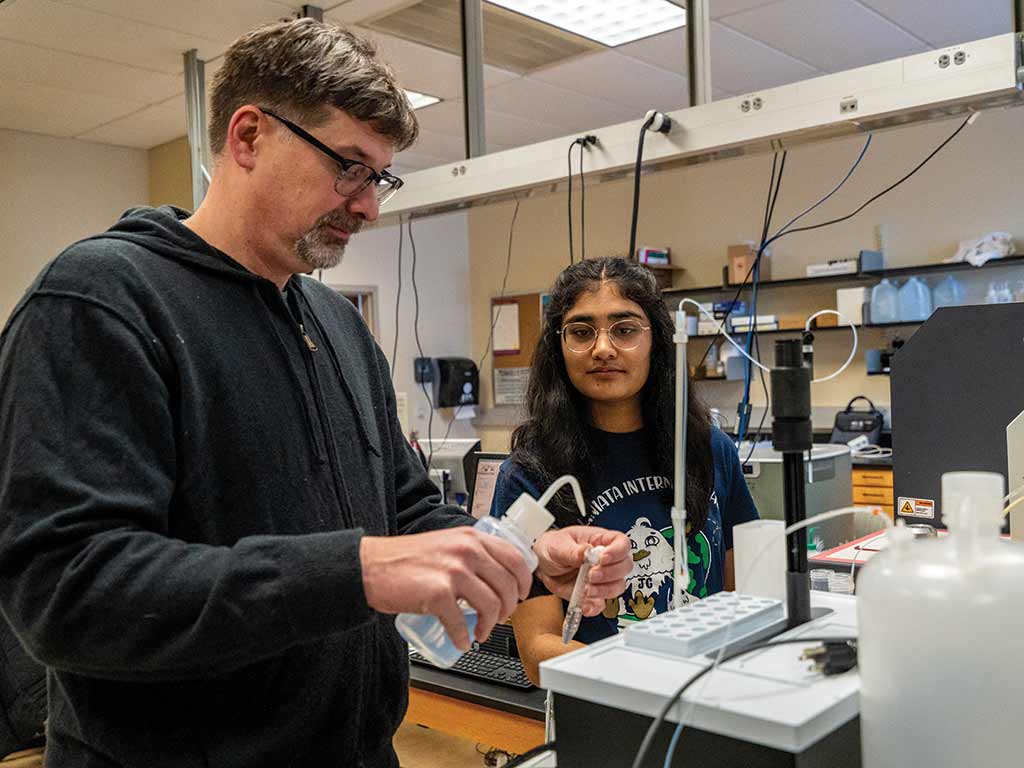

Juniata recently added an IC PMS Multicollector to its assemblage of technological devices. The instrument is used for high precision isotope ratio analysis of liquid and soil samples. Ryan Mathur ’96, professor and department chair of geology, said he’s used multicollectors in labs all over the world. While they typically cost more than $1 million, “Luckily Penn State was getting another one and I was able to get this one at a greatly reduced price,” he said.

In his Environmental Geochemistry class, Mathur takes students to mining sites where they use devices to take samples of the groundwater and surface water. They return to the lab and make their own measurements, interpreting and analyzing the information in reports.

“It’s an eye-opening experience for the students,” Mathur said. “One, they get to go out and collect the information. Two, it kind of goes against what they were initially thinking they’d find. I do that on purpose to show that you have measure and figure stuff out.”

As he continues, “The students get the opportunity to practice science while using the instruments. So, it’s much different than typical science classes.”

Instrumentation has a heavy presence in other classes, including Geoarchaeology where many students might not be as familiar or comfortable with the gadgets.

“There are historians in there, game studies people and museum studies people,” Mathur said. “I make tasks for everyone to do and then rotate them around, so they get a chance to press the buttons and do stuff, see how the numbers are generated.”

Juniata’s technology lets students glean results from their samples in person, instead of waiting for data sent back from an outside lab. Mathur said the discovery process is enhanced when it occurs in real time, like when his class returned from a field visit with three different types of metal.

“We had no idea,” he said. “We thought they were all lead but we found out some were zinc and the others were mixtures of zinc and copper and zinc and iron. Everybody was going crazy because they didn’t understand. Everyone was thinking it would be all lead.”

The immediate connection between samples and data leads to better work on both ends. “Seeing the results happen even though they might not understand everything makes it more real,” Mathur said. “And you see it in the output, too... The reports are far superior with the stuff that we collect now.”